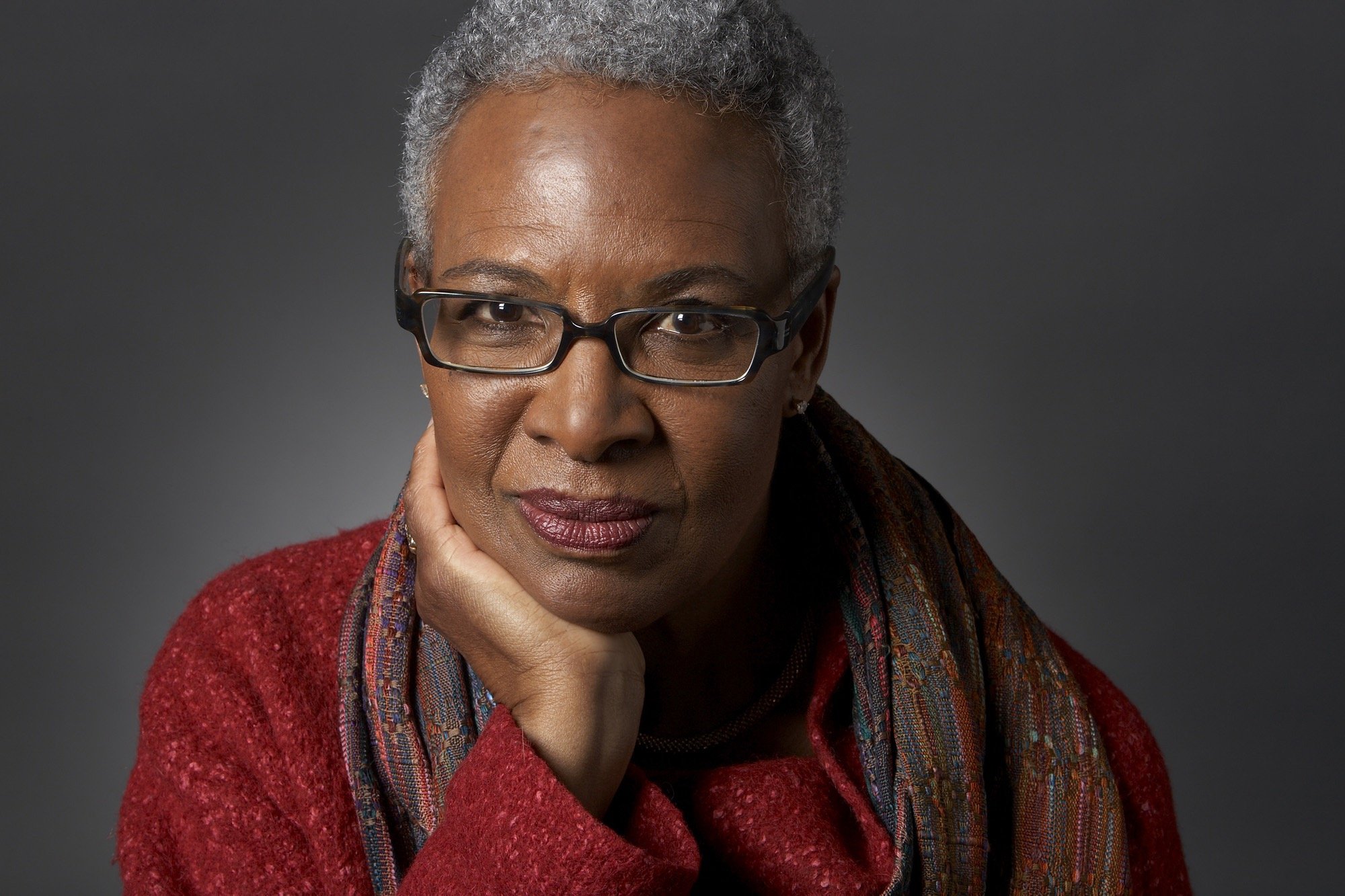

Nell Irvin Painter

Henry Louis Gates Jr. refers to Nell Irvin Painter as “one of the towering Black intellects of the last century.” I first heard Nell on Scene On Radio with John Biewen in his series “Seeing White,” and have been biding my time for an opportunity to interview her ever since. I got my chance, with her latest endeavor, an essay collection called I Just Keep Talking, which is a collection of her writing from the past several decades, about art, politics, and race along with many pieces of her own art.

Now retired, Nell is a New York Times bestseller and was the Edwards Professor of American History Emerita at Princeton, where she published many, many books about the evolution of Black political thought and race as a concept. She’s one of the preeminent scholars on the life of Sojourner Truth—and is working on another book about her right now—and is also the author of The History of White People. Today’s conversation touches on everything from Sojourner Truth—and how she actually never said “Ain’t I a Woman?”—to the capitalization of Black and White. Let’s turn to our conversation.

MORE FROM NELL IRVIN PAINTER:

I Just Keep Talking: A Life in Essays

Nell’s Website

Follow Nell on Instagram

Scene On Radio: “Seeing White”

TRANSCRIPT:

(Edited slightly for clarity.)

ELISE LOEHNEN: I loved this collection of essays and we'll get to Sojourner Truth because I heard you on the Seen On Radio, I loved that series that you participated in on race, it's old. Do you remember that whole series that he did? No.

NELL IRVIN PAINTER: No.

ELISE: But that's where I first heard you. This was six years ago, maybe, talking about Sojourner Truth and the way that she had been mythologized and what the implications of that are. So we'll get there.

NELL: Because I'm still talking about

ELISE: that.

I know, I think it's really interesting, the nuance of why it's important and I love that about your work in general, in the short essay about affirmative action...

NELL: that is so old, that essay.

ELISE: And it holds. That's what's so fascinating about so many of the pieces in your book, like the piece on reparations that you wrote, and I was like, Oh, when was this? Like, 2020? And it's like, No, 2000.

NELL: Oh, yeah.

ELISE: Yeah. But affirmative action, and you write, I have benefited from affirmative action, because were you the first black person and first woman or first black woman...?

NELL: No, in the Penn History Department, there was a black male faculty member who was very much involved in getting me there. So I was the first black woman.

ELISE: Got it. But that idea, like, it was interesting to hear you talking to students who essentially were like, I hate affirmative action because everyone assumes I don't deserve to be here. Or what happened to you probably in terms of prize selection for your books? Like this can't possibly be at the equality because she's benefited from affirmative action. But without things like affirmative action, we can't recognize...

NELL: we can't see people. We can't see people.

ELISE: We can't see people.

NELL: And that's something that I think is really dare I say, encouraging about the time we're in now that we can see people who could not be seen 20 years ago, maybe even 10 years ago, so I was on a list of the 45 best books this season by authors, by women of color. And I thought 45 books by women of color, you know, we won't even talk about whether they're the best or not, but just 45 in one season to me, you know, where I came from and how long I've been at it, that's just so encouraging. And then on the other hand, there are all these people, I know you see these in the book reviews and all this, Oh, publishing is just going to the dogs. It's not like it used to be when editors would stick by authors, even if they weren't bestsellers. And I'm thinking, Oh, those were white guys. They were white men. When do you hear about sticking next to an author, a woman author, an author of color in those days? No. And I'm not an Afro pessimist. I think things have changed. That's not saying that we don't need a whole lot more change. We do. We do. But things are not like they were a quarter of a century ago, not to mention half a century ago.

ELISE: Yeah. I mean, so much of our most horrible history is just in the rear view mirror. If we're honest, I mean, and it's still happening. Let's also be honest. But I agree and I don't know if you feel this way, but It's interesting who has taken up the mantle and I want to write about race and the capitalization of white because you painted it so well for me in the context of like, white people need to be racialized in order to understand race and yes, we don't like it and it's so weird, but if you just assume it's the default and everything else is aberrant or other, then you're in a strange space.

NELL: Absolutely. And the big thing is that the assumption is that white people are individuals. So there's no community to feel responsible for or to feel like you belong to if you're just an individual, it's just you out there by yourself. And in some ways that's harder because all the stupid things you do, you know, they're on you as opposed to thinking about what the culture is like or what the society is like, or having the tools to grapple with when you're treated unfairly.

ELISE: What you said just lit something in my brain on fire too, which is that it feels like an unlock, I'm curious what you think, but this idea that white people are so individualistic, That then too, when we are described as collectively racist or involved in these systems of oppression, we internalize that as individual shame. And I think that's why the tolerance for it becomes so splintered and projected, because we don't know how to share responsibility, and we don't know how to deal with, I think for women in particular, I wrote a whole book about women and goodness, like, I'm a bad person? I've perpetuated this? I think it is why also we break instead of seeing it as a systemic issue. Our first instinct is like, you're talking about me.

NELL: Yes. And then to be very defensive. And I don't understand, you're explaining it very nicely, but I don't understand why there is so much Republican pushback against critical race theory, because critical race theory actually lets individual white people off the hook. It says the system, but it's just maybe it's just the whole idea, the whole miasma of race that, I don't know...

ELISE: I think it's because we feel, it was interesting when you were writing to about in the essay about Sojourner Truth, I think it's in that essay about how like one of the currents of that conversation historically was that it was much more interesting or engaging or enraging to talk about people who were actively enslaved and that there was like this lack of interest in people who were free but suffering. You can say that that's true today. I think it's because in part that anxiety of like, Oh, well, am I like doing that is so unbearable for I don't know. That's a projection into history.

NELL: Yeah. I wrote a piece in the New York Times many years ago. I can tell you when it was. It was 2015, because it was when that Nazi confederate slaughtered all the good people in Mother Emanuel Church, and I said, you know, white people need some other words, because the Nazis and the white supremacists and the nationalists have commandeered white identity. You know, they really spoiled it. But we also have another word from the 19th century, which is abolitionists. And, you know, you can't just say, Oh, I'm an abolitionist and not do anything. But if you know that there is a role, there is a place for anti racist white people. And there's a name for it: abolitionist.

ELISE: yeah, I thought that whole piece, I don't know if it was from specifically from that New York Times piece, but this discussion of race where you talk about how white people need to be racialized in order for this to become like a coherent narrative.

NELL: capitalized white.

ELISE: capitalized white and it's so fascinating to me because I think then, of course, people bristle and I think you write about this and history of white people and you mentioned it here that this idea of being called a Caucasian is actually so strange, right? That we're all Chechen. But that this lack of nuance, and you talk about in the context of brown people too, like, that's a big umbrella, right? For people who are from wildly divergent cultures. In your mind, as you think about moving us forward and the history that you've studied throughout your life, do we become more specific or do we need to stay in the less specified? You talk a lot about like specificity versus...

NELL: I do.

ELISE: generalization. Yeah. Can you explain that?

NELL: I'm all for specificity, because lumping us in these groups of people that number in the millions, you know, it doesn't make any sense. And for the longest time, I felt that people wouldn't pay any attention to what I was saying because what I was saying wasn't just about Black people, but it's like Black people are only supposed to talk about Black people. In the 20th century, white people felt free to talk about anything. White men could talk about anything. I think that's less the case now. I think there's more care. But, you know, I have always felt that anybody could write about anything and anybody could publish anything. The next step is the important one, which is getting published. Getting published by a publisher who can put your book in the world. Getting published by a publisher Who can put your book in the world and promote it. Getting published by a publisher who can put your book in the world and promote it and make sure you get the reviews and the attention you need. It's that tail there that was missing because women, Black people, Brown people, Native people have been telling their stories, not just for decades, but for centuries. But they have just slumbered in the archive. I'm writing a new book on Sojourner Truth that took me back to the American Antiquarian Society last year. And the American Antiquarian Society on their website has a special place for Late 18th and 19th century authors of color, and they have something like 565 titles.

ELISE: Wow.

NELL: Yeah, I mean, I don't know if Frederick Douglass is in that. I mean, he's just so unusual in that we still know his name and we still know his books. But most of those 19th century writers, their books are just in the repositories. I mean, we've come a long way in the 21st century, starting in the 90s, I think, of republishing, reprinting older materials and getting them in the world. But the idea that people of color have been mute until now. No, no, not at all. It's the infrastructure of getting works into the world.

ELISE: So let's talk about Sojourner Truth and the way that you describe her as being sort of flattened by this phrase that she didn't actually say. And you take a lot of pains to try to clean this up in culture.

NELL: nobody paid any attention to me at all. That's not quite true. It is getting some attention now. But There were three scholarly biographies of Sojourner Truth in the 90s and the first decade of the 21st century, and we were all very careful to show that Frances Dana Gage made up this refrain that she has Sojourner Truth repeating four times, which is not at all in the contemporaneous report. If Gage had only had Sojourner Truth saying, "aren't I a woman" once. I would not have felt so sure, but it's a very dramatic scenario, and I think that's what's made it so much more interesting than the contemporaneous one, which is in standard English. And I think even now the great American public doesn't want to read 19th century Black people in standard English because it's not authentic.

ELISE: Yeah. And in the sort of myth making or legend making of Sojourner, who also spoke Dutch, as I learned from you. Yeah, Dutch and standard English that, yeah, that this whole speech that there are parts of it that seem like. echoes of what she said, which was still compelling.

NELL: the meaning is there.

ELISE: Yes.

NELL: Meaning is there. I don't want to take Anything away from the meaning, because what we now call inter... no, that's not right.

ELISE: Intersectionality?

NELL: Yeah.

ELISE: Intersectionality. Yes.

NELL: So, you know, it's more than one identity, we still need that. We really, really do. And that's what she was talking about, but not in those words. And the words are so convenient that people have just latched onto them without feeling they needed to know much more. Okay, Sojourner Truth had been enslaved, therefore she was a Southerner, right? No, she was a New Yorker. And so my new book's title is Sojourner Truth was a New Yorker, and she didn't say that. And it's going to be biographical essays, because I already did the scholarly biography. And I'm going to have one chapter on Sojourner Truth, knitter.

ELISE: Sojourner Truth, she was a knitter?

NELL: don't have that book in front of me, but the most famous photographs are her sitting with her knitting in her lap. And she decided how she wanted to be seen.

ELISE: Yeah. So interesting. I was just interviewing this journalist, Maddie Kahn, who wrote this book it's called Young and the Restless. And it's about teenage girls throughout history, but it's also about the way that we just love to find the one to carry the banner and how that in turn flattens the other people and it's just much simpler, right, for us and our narrative, but it is very pernicious, because it suggests that everyone else's contribution doesn't matter, or that if you're not the one that somehow carries the headlines, that your work isn't impactful, and then we lose out on a much more nuanced and compelling history. So besides just like wanting an accurate representation of history as a historian, what else about the Sojourner Truth flattening by Gage bothers you?

NELL: That's all that the work of art. I mean, Gage was a journalist. She was an artist. That a work of art has been substituted for a person and offered a means not to go any farther.

ELISE: Mm.

NELL: And so I have this innocent thought that If I can let people know that there's art involved in Aren't I or Ain't I a Woman, and that we can know so much more. So what I want to say in my new book is the so much more. So, for instance, the introductory chapter is about monuments. So much more. That's what I want. So much more.

ELISE: And which I think too is an invitation, I don't know what the invitation is exactly, except that all people are more complex, right? And all stories are more layered. And heroes have shadows. And people who we have rightly or wrongly, also maybe had some redeeming qualities. Like, there's something that's in us that's so inclined to be reductive. I don't know if they were wired like that. I don't know if you have a theory about this, like, that we just want simplicity? It's just easier.

NELL: I don't have a theory. And certainly I have nothing original to say, but, you know, having lived a long life and met so many people, it's like my little brain can't hold infinity of individuals whom I need to interact with. And so, you know, there are little boxes that people get put in and all the people in that box, well, so for instance, we lived in Newark, New Jersey for a long time. So I have a Newark box It's not so many people that I can't tell them apart. Maybe if it's the Princeton box, or the New Jersey box, or the New Jersey Turnpike box, but there are just too many people to keep up with all the details of the specificity of all the people. And also we don't need to have the specifics of everybody all the time.

ELISE: But I love the idea, like thinking about you describing that. I lived in New Jersey for a few years too, but not my primary identity. But I'm from Montana and from a specific type of horse culture in Montana in some ways or adjacent to that. And it was interesting because I just a few years ago went back and back into that horse culture and it was such a somatic experiencing of like, I understand these people. And much more prominent, I think, in my identity than so many other parts of who I am, and highly specific. I mean, my husband doesn't understand it, right? But it's hard, I think, in our culture where We're trying to determine all those lenses through which we see the world or those experiences that have shaped our worldview while still holding on to a collective story. Or figuring out how we all relate to each other. I don't know why that work seems so difficult? My cat wants into this conversation.

NELL: C-Span came out to talk to me up in the Adirondacks actually, it was a beautiful snowy day, and we had cats then, and I had one tabby cat who was very beautiful and knew it, and he just walked all over, he said, hi, You need to see me. Why are you talking to her? I'm so much more interesting..

ELISE: think my cat heard me say horse and was like, whoa, I am a cat person. Fine, you win.

NELL: I feel strongly about specificity because I mean, it's very personal. So, I'm from the West Coast. I'm from Oakland. And you know, I moved to Oakland as a tiny infant in my mother's arms. So I'm a Californian. I am not a Southerner. I lived in North Carolina for several years in the 80s. And it just, I am not a Southerner. And I think I thank my parents in the introduction for taking me away, I could never be a Southerner, but so much of what is considered authentic Black identity is Southern, is having working class parents, is being the first person To go to college or to even go to high school, are generalizations that don't apply to me. So for many years, I felt that people would not want to listen to what I had to say, because for one thing, I talk about white people as well as black people, which already is a departure. And I think I have a kind of strange position as a Black author, when my best known book is called The History of White People.

ELISE: Well, I feel like it takes outsiders to really understand the insides of other people's culture. I think women understand men a lot better ...

NELL: oh, yeah. Yes.

ELISE: Yes. I wish men had the same curiosity about women. No, and it's true. And I can say as a white woman, the Karen-ification of culture hurts, you know, it hurts and You want to do anything you can to distinguish yourself as not that and then at the same time try to figure out, like, instead of using this as a cover for misogyny, which I think it sometimes does, what would it be like to sort of not deprecate each other and find, what's happening? Why can't we get on side with each other and our collective interests across any identity.

NELL: I don't think we can move, act, think with any. We can only do that, I think, in specific situations with specific people. But one thing the whole Karen thing did, which I think was very good, was that it pointed out the existence of spaces Ostensibly open to everyone, but not, and then patrolled often by white women saying you don't belong here. And she got a name, and people with that name wince and rightfully so, but without that wince worthy kind of situation, I don't think large numbers of Americans would realize that there really is a sort of silent apartheid in our public spaces.

ELISE: That's really interesting. I hadn't thought about it like that. And do you feel like the Karens are the ones who are, like, the patrol people for that? Or the most overt?

NELL: Yeah, I mean, to my mind, the, the sobriquet, so it's a sobriquet, it's not somebody's real name. I mean, it is some people's real name, but the character...

ELISE: yeah.

NELL: the character, what she does is police public space

ELISE: Hmm.

NELL: against people of color, against black people.

ELISE: Hmm. Interesting. I hadn't really thought about that. I mean, you talk about these sober kids in a fascinating way in the essay about Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas and how there were no avenues because there were no shortcuts. There were no cultural stereotypes or shortcuts for her, right? Outside of, I think you called out the mammy, the over sexed Jezebel.

NELL: And the welfare mother. Yeah, and Thomas evoked that stereotype against his own sister.

ELISE: Mm hmm. I had never knew that.

NELL: Yeah, I remember it at the time, and it was just enraging, and all you had to do was ask one or two questions about the sister to discover her story is legion for American women. She put her own life aside to take care of her family. And she fell on some hard times. And she didn't use public assistance any more than was necessary, but he turned her into this despicable stereotype. I mean, he's a terrible man.

ELISE: Yes. I know. It's interesting. I read that essay and then I went to a book party for Christine Blasey Ford. Anita wasn't there, but she sent remarks to be read. But it was interesting thinking about those two as well and I think how there was like a stuttering around like what the stereotype of Christine Blasey Ford, it was like a short circuited, well, I don't think it short circuited the brains of many Americans, but clearly it was like, how do we categorize this very qualified, highly

NELL: qualified...

Yeah.

ELISE: incredibly contained professional woman who has nothing, nothing to gain by doing this. But it's interesting how absent those tropes, we don't know what to do. And then you wrote about how Clarence Thomas so deftly used those tropes, sort of the witch hunted black men, and the race traitor against her and the culture at large. Aye, aye, aye. How conscious do you think that that was for him? Like, do you think that he just understood culture so well that he knew how to play it?

NELL: Either he or whoever was advising him, but the turned inside out charge of black beast rapist, I think a lot of Americans understand that that's a charge lacking credibility so that we feel, we automatically feel more along with the person charged with rape because we suspect that the charge is false.

ELISE: Yeah. And the race trading, I mean, I wrote about this a bit in my book, but the reality of sexual assault crimes, the only instance where this doesn't hold is with Indigenous women, because fracking camps and these man camps and the way the tribal law intersects with federal law just creates this like giant vacuum in which all these indigenous women go missing and are murdered. And it's horrendous. And so the only bit otherwise, Rape or sexual assault, for the most part, is not exclusively, but almost entirely intraracial. And so all of these ideas, and we get them on TV shows and in the media, that, you know, this idea of a menacing black man who's out for white women does not correlate with statistics. White women are typically raped by white men.

NELL: Right. Yeah.

ELISE: often like domestic or people that they know or know slightly That's the story of sexual assault, but he also played that quite exquisitely against Anita Hill.

NELL: Yeah.

ELISE: Do you think that that's as pernicious now as it is it was then?

NELL: No, I don't think so. I mean, just look at the role of Joe Biden who was the innocent white man at the time. And Clarence Thomas could get away with it because he was facing a roomful of white men who hadn't a clue about how race and sex work in the world. So they were taking everything he said face value because they didn't know any better. And now, if such a thing were to happen, there would at least be Cory Booker there doing something.

ELISE: Yeah. Do you think like going back to this idea of like tropes and And stories that are, I'm trying to think of this research, I just read this neuroscientist book and it was about sort of the upside and the downside of stereotyping in the sense that like stereotypes often can be true. They can be used very perniciously. But that when we create this idea, like the Karen, et cetera, that there's like a fair amount of truth in these stereotypes. How do you think that that with the specificity, do you think that we widen them to the point where there are enough avenues or do we eventually explode them through specificity?

NELL: I think we just leave them by the wayside if they're no longer useful.

ELISE: Can move past them and abandon them?

NELL: The great lesson of the history of white people is that things change. But the great lesson of history of life is that things change. The language changes what we assume changes. You know, how many times have you told a young person, you'd CC them on an email and then come with a clue as to what you're talking about, you know, hang up the phone, what? You know?

ELISE: Oh, God. It's true. Or counting your text minute being like, I can't text you because I have to pay 10 cents or whatever.

NELL: Oh...

ELISE: Hit your overage on your texting? Oh, that was. That put me in debt in my 20s.

NELL: No, I didn't start texting until recently.

ELISE: It's funny that we started the conversation though being like, nothing, I mean, in some sense everything has changed and nothing has changed, but I feel like so much of this doesn't change necessarily in our lifetimes. Maybe?

NELL: Everything changes. That's my motto. I mean, as a historian and as an old person, because there's so much that I grew up with, that just doesn't apply anymore. You know, I was young in the 50s. Thank God it doesn't apply. I would never go back. But it also means that things go around and so questions come back that were sorted out in the 60s, but all those people are dead now, and so we have to do it again. So there's a lot of reading I don't have to do because I did it, you know, 50 years ago.

ELISE: Yeah. Do you see like things repeating that you are like, of course, this isn't resolved, so it's come back to be reprocessed and re litigated, or are there things that you're shocked to see them? I mean, it's shocking in some ways.

NELL: Well, what is shocking is the return of book dates. That really is shocking, and it caught me by surprise. And I wonder how successful it will be. I see that Governor DeSantis is not carrying on with anti war, but, you know, evidently that has lost some steam. And I hope that is the case. What I wonder, you know, I see a lot of people, or know of a lot of people who are in positions of power while being Black, even being Black women, and on the one hand, we bring our hands over Claudine Gay, who I think really was Targeted as a black woman. And I think the three college university presidents who, at least the phonic ambushed were ambushed as women, but at any rate, there are so many women, black women, black men, people of color, all around our public life. I wonder, you know, can there be another retrenchment, like after Reconstruction, with so many people? And I want to say, there are too many people in too many places for our public life to survive their removal. And I think enough Americans of all backgrounds are understanding that, but I'm not sure.

ELISE: Yeah. And you could say this isn't true, but there's different types of power that are distributed slightly more evenly in culture, particularly now that everyone can publish in some ways or reach audience, more eyes watching, etc. That it does feel like a total rollback seems impossible. I mean, but we are in really strange times. That's for sure.

NELL: Yeah, I was talking with friends yesterday, I got an award from Ava Shalom, the only synagogue left in Newark.

ELISE: Mm hmm.

NELL: Newark is a wonderful place. It's like one third latin one third black and maybe 20 percent white or something, you know, and people are used to dealing with people different from themselves in terms of their racial ethnic identity. So it's really nice. And there were lots of people, was talking to a friend, you know, everybody's Wringing their hands about the election and how terrible and there's so much hatred and all, and it's as if you declare yourself a naive, dumb person if you're black and say you're an optimist. I would never say that. I've just lived in this country too long to be an optimist. But on the other hand, I do believe in the possibility of a breakthrough, of a turning back, and of a sort of self combustion of Trump. There's just so much going on there, and he is more and more incoherent and stressed with money and all that, and I see Trumpism as a movement, you know, kind of as a religion. And one of the religious parts of Sojourner Truth is Millerism in the 1840s. All these Americans, thousands of Americans, believing the world was going to come to an end. And we do hear apocalyptic phrases from Trump. In the 40s, God and Jesus did not come back in 1843 or 1844. And there followed the Great Disappointment. And I'd be surprised if such a thing happened again.

ELISE: So interesting. And I'm with you. I mean, I do feel optimistic that despite feeling like we can be regressive and that but that we're making progress and our consciousness generally is lifting, and we're more aware of ourselves and other people in our stories. And I also think that there's an implosion, that we'll look back at this in some way and say look what resulted is ultimately going to be positive, which sounds perverse, but that it's painful, but that somehow this was pushing us forward in a way that was woke us up, brought us out of complacency, made us pay attention. Like this matters. Like the Supreme Court sure matters. And not that not that we can all stay in a state of hypervigilance. I don't think people's nervous systems generally can handle that. And we need a cogent, coherent, functioning government. I think even the people who voted for him in 2016. I'm gonna guess that many of them are like, I don't need that level of chaos. I just don't. The world is chaotic enough.

NELL: No, there are more of us than there are of them. In 16 and 20, the popular vote was four. Democratic candidates. And if you look in California and also in New Jersey, if you look on the state level, things are coming along. We have a very interesting special, no it's the Menendez seat in the senat and they're calling him, they insurgent candidate. He's not he's a good Democrat. But the governor's wife, Tammy Murphy, jumped in months ago saying she was going to run for Menendez's seat. This is a woman who has no experience and who gave money to Republicans until yesterday. And I remember thinking, you know, I'm tapped out. I give money to my regular Democrats, you know, month in and month out, but I get a trillion Democrats sending me texts and I send "Stops" back to all of them. But I didn't do that for him. But it turns out that thousands of New Jerseyans felt the same way. So he's got all this money, and she just left the race. So, you know, on the local and state levels, I just told you about the synagogue. And then, of course, there's this election. So, you know, if you can kind of focus Closer to home, and if you're in a place like California or New Jersey or New York, I don't think you need to go wringing your hands and, oh, woe is me, at least not yet.

ELISE: Yeah. Well, and I think that Keeping it close to home, because I think this has also been a lesson for people in like, Oh yes, federal government matters. Yes, like on a level of global chaos, but actually, your rights are protected on in the state level more and more and that that's where we need to be paying attention. So in some ways, I think everyone got a real crash course. I mean, maybe I'm just projecting, but a real crash course on government and that I think it will serve us well and I think that people will is horrible and painful as it has, and tough on every level. I mean, COVID, all of it, it's been a wild ride...

NELL: On what you're saying, you remember in 2016? A lot of us went around saying the Supreme Court, the Supreme Court, and not enough people paid attention to that. They know now.

ELISE: Yeah, they know. I don't know when we will be able to return rights to people, but oh man, and I know Clarence Thomas, we'll just finish on Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh, it's wild.

NELL: the guys.

ELISE: The guys. Oh, well, thank you. I loved this book.

Nell Irvin Painter is a prolific, prestigious, historian, and writer, and I love that in this book, I haven’t read everything she’s written but she’s just so wonderfully straight forward. She’s at a point in her life, she’s 81 years old, where she just says the things, which I find relieving and refreshing and it’s so nuanced. We didn’t get to it really but there’s this essay about the idea of enslavement, again she’s a history professor so she really cares about the specificity of the way that these words and ideas are used. In that particular essay she talks about how in 1619 Black people were not enslaved yet, it was a process that took place of turning “servants” from Africa into racialized workers, enslaved for life. That this was a slow burn process and then she expands to talk about how across the globe, she writes: “Raiding for captives to sell belongs to a long human history that knows no boundaries of time, place, or race. This business model unites the ninth-to-twelfth century Vikings,who made Dublin western Europe’s largest slave market (think of Saint Patrick, who had been enslaved by Irish raiders in the fifth century), and tenth-to-sixteenth century Cossacks, who delivered eastern European peasants to the Black Sea market at Tana for shipment to the wealthy eastern Mediterranean.” She’s trying to revive and push air into history so we can look at its complexity and nuance, rather than flattening it, as she says, looking for all these tropes, which are always more complicated then they first appear. The book is called I Just Keep Talking, it’s her essay collection. As she mentioned, there’s a raffle for one of her books in her print, she’s an artist, I think she has one of her books coming out shortly about her work in art. So the book includes a lot of her art, which is really fun. Alright, I will see you next week.