Matt Gutman: Contending with Panic

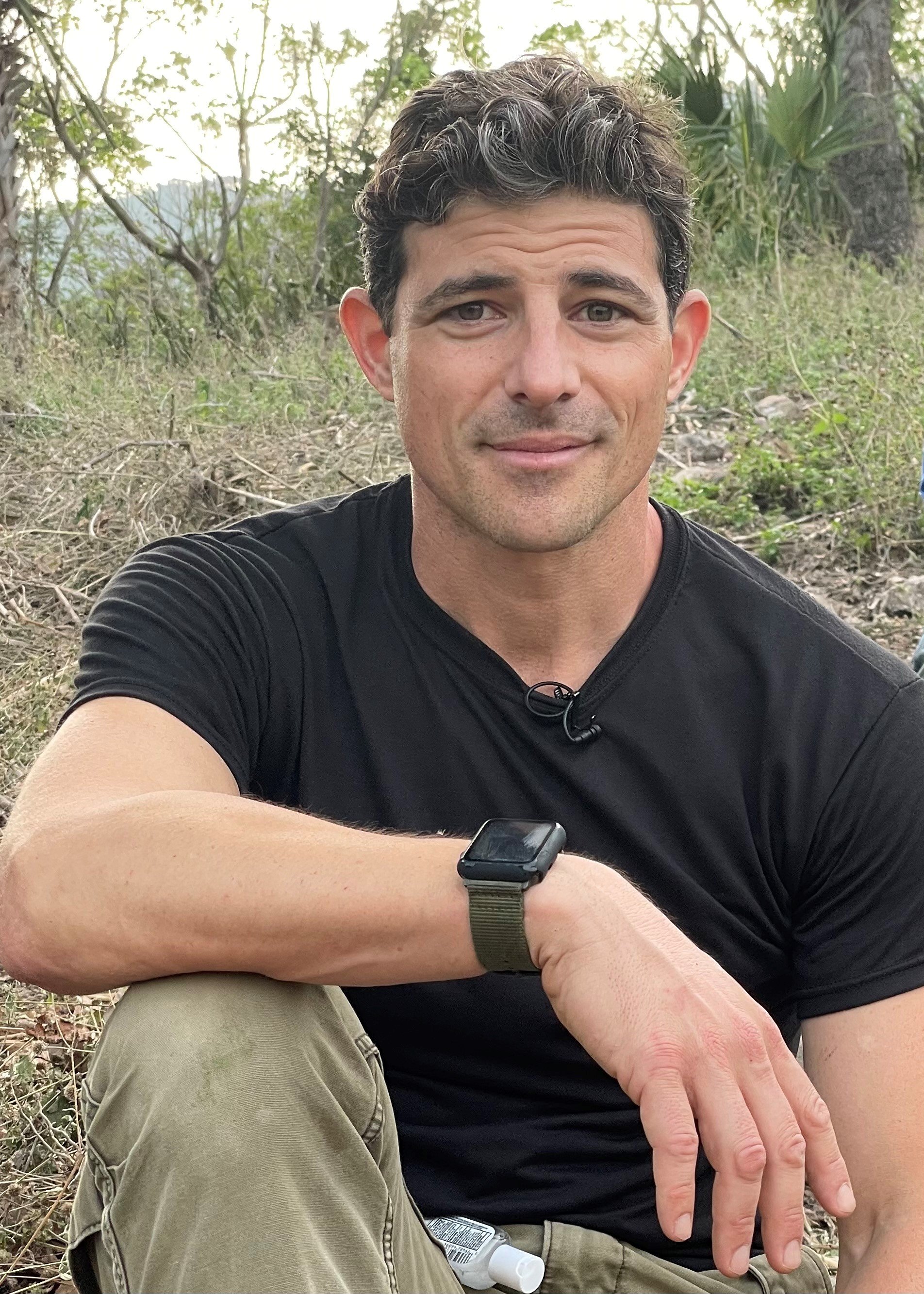

Matt Gutman is an ABC Chief National Correspondent and the author of No Time to Panic: How I Curbed My Anxiety and Conquered a Lifetime of Panic Attacks. Matt is a new friend, and I’ve loved getting to know him and his deeply feeling heart, as well as the way he so perfectly captures this idea of being a “courageous coward.” He’s not afraid to step into a war zone, and yet he’s felt incapacitated by anxiety—taken out at the knees by panic—which makes him the perfect encapsulation of the binary of modern masculinity. Quite simply, the world is too much for any of us to confidently swashbuckle our way through. I commend Matt for saying it. He wrote this book because he suffered a panic attack on air during a heightened moment of news—one of those moments where all of our eyes were turned toward our TVs—and he ended up being put on a temporary leave. It was in that moment that he recognized he needed help and healing, as this panic attack—though public—was not a solitary event. It was happening to him all the time. In No Time to Panic he explains how hard he went to work at healing, at uncovering what was at the heart of his anxiety, which is at the center of our conversation today.

MORE FROM MATT GUTMAN:

No Time to Panic: How I Curbed My Anxiety and Conquered a Lifetime of Panic Attacks

Matt Gutman’s Stories at ABC

Follow Matt on Instagram

TRANSCRIPT:

(Edited slightly for clarity.)

ELISE LOEHNEN: It's funny, thinking about my own book, your book to me was the perfect end cap, it’s an extension of the final chapter, which is about sadness and men, and what happens when men are severed from their feelings, disconnected, disallowed, and as you seem to find the only cure for sadness is grief, but it can be inaccessible, right. So take us back to, not the inciting event, but this idea that you're enduring panic attacks, which started, was it in your twenties?

MATT GUTMAN: I actually now think that I had started the panic attack started in high school. I was, you know, a massive high achiever and, you know, felt like I had to excel in everything, so was school council president, and every morning I had to deliver, I don't remember what it was, but like, you know, a few sentences to the school about the day's activities. And I didn't exactly know what it was that I was feeling, but they were pretty much panic attacks. But the first full on, like sweat through my shirt, molting into a werewolf on a full moon meltdown, panic attack was in college delivering my, my thesis, my college thesis. And the thing is, Elise, it wasn't mandatory. It wasn't graded, it didn't count. I was done with school, basically had graduated, I had my GPO, I just had to tell, You know, the people who I was closest to in, in the political science department and the faculty about this thing I've been working on for a year. Like, I knew it cold. Like I could not have known anything better, and I stood up there, well, I even before I got up, my heart started pounding, and I was like, oh, that, that's quite curious and a little bit uncomfortable. And then I somehow hovered to the podium and then I started white knuckling it, because I couldn't breathe and I couldn't talk and I couldn't remember what I had to say. I only know that what I likely said was pretty dumb and generic, because I can't imagine having produced any clever thoughts in that state and so like, I don't remember what I said. I don't remember how long it lasted. I just remember going back down into the seat and like feeling like I'd fallen through the floor being completely wet.

And I never addressed it again until later when I began working as a journalist. And I, you know, never had a problem as a print journalist, but when I started doing radio, I started having that strange sensation that I'm about to fall through the floor. And, you know, all you have to do in radio is read the copy on the sheet in front of you and I'd be looking at the sheet, you know, sometimes I would be out in the field, my first radio hit was in Gaza, but I'm like holding it and it's shaking and suddenly words are magically disappearing from the page and I'm skipping over them and unaware of what's going on, and so for many, many years I didn't realize what this phenomenon was until like the 2010s and I started doing TV and a few years into it, I'm like, oh, I'm having regular frequent panic attacks. A lot.

ELISE: Yeah. I wanna go back into that, but it's interesting and you touch on this throughout the book, but the mechanical actions of the body, because I don't have panic attacks, but I have my own anxiety disorder. And I've certainly done press where I'm like, I blacked out. I have no idea what I said, but I know it well enough that I just can move through it. You would never look at, I look calm, right? I don't have a sweating problem.

MATT: Hey, too soon, too soon.

ELISE: But that the body is mechanized, I mean what's so interesting, I think, and you distill this I think really beautifully in the book, is that anxiety becomes like a full embrace. It's mental, emotional, sometimes spiritual and physical. And so understanding where it's coming from, what's driving it and how to stop it becomes like untangling a massive knot. And it feels so physical. At least when I had my, was first diagnosed with my hyperventilation disorder, I wanted a physical cure. You know, I didn't wanna hear that it was just this not local anxiety driving me to the place where I was over breathing and feeling like I was gonna suffocate, you know, all of it, all the stuff that, you know, intimately. They ran checks on my heart. I have subtle asthma, yada, yada, yada. You can imagine. But I couldn't locate the anxiety, right? I couldn't say, oh, it's this inciting event that triggers this. It's this toxic stew of over caffeination, sleep deprivation, anxiety of some sort of, I still don't know what it is. And like you, I've been driven to understand it on a much deeper, potentially spiritual level because there's no single, as you know, I mean, you kind of know, but then at the end you recount having a panic attack in a completely different way, right? Like, if we knew it was always gonna happen because of these factors, then you can control the factors. But the unpredictability of it is what's so dis disorienting, I think.

MATT: So just to step back, like you've blacked out doing an interview? Did you have hyperventilation? Because those are two of the major symptoms of a panic attack. That's pretty much a panic attack. That's what happens to me. Like I've had them and I've, including the one where I had this, you know, the, the reckoning that nearly destroyed my career, but I literally did not remember what I said. And I was called by someone very important at ABC at and at Disney at the time, who was like, did you just say what I thought you said? I'm like, I have no, I have no idea what you're talking about. And then I, like I was told you said that and so blacking out is definitely, and we'll get into the chemical stuff of it cause it's super interesting. But the blacking out is definitely a major symptom.

ELISE: Yeah, I mean, it's not uncomfortable for me the way that it is for you, and it doesn't seem attached to fear, and I've worked through a lot of it, not through the hacks, like the lucky underwear and stretching and distraction that you write about, but for me it's been maybe exposure therapy. I remember the first time I ever hosted panels in a live event and just feeling like I did a pretty terrible job. The audience might not have noticed, I think I passed a low bar, but I had recognized like, until I could find a way to be comfortable and present that I would find the whole experience incredibly depleting and exhausting, which is how I felt that day just physically destroyed by the act of trying to move a panel forward instead of letting it evolve and then when I do press, I don't lobster claw the way that you write about that. It's more that I'm like, I don't know, I think I hit the points. I think I did well, I have no idea. I couldn't necessarily remember or recreate the conversation. Does that make sense? I actually need the validation of someone listening to say like, did I make it through the material? Because I don't know.

MATT: Sounds like a highly anxious experience, but maybe not a full on, you know, sweat through your socks. You know, I'm having a heart attack, panic attack.

ELISE: Yeah. I did have one of those in the subway in New York once.

MATT: This is one of the interesting things about why I wrote this book, you know, I think of someone like you and, and you just posted these videos of yourself on a very large horse riding really, really fast through trails on which they're, you know, are basically a tunnel of trees and then like off like a mesa somewhere where you could have fallen like a thousand feet down in a tumble and easily killed yourself. Oh, but you're wearing a flimsy little cork helmet or whatever helmet you wear as if that's my save your life. You know, which most people are like, that's insane. You're galloping on a 1200 pound horse at top speeds, you know, through a place they could easily be killed. And I think a lot of us embody this, what I call the paradox of the courageous coward, right? Like, we're capable of doing these things that are bonkers. Like they take a tremendous amount of courage or maybe experience, you could call it, but we'll call it courage, speaking in front of a panel, going live on television, you know, with me, swimming with sharks, going into the eyes of hurricanes, going to war many times, marooning myself in weird places. And yet we have this other side that is like so fragile, so gossamer thin and on our level to tolerate anxiety that, you know, it can break and then snap at any moment.

ELISE: Yeah, a thousand percent. And I thought that was so beautifully told, the difference. And yes, like I do things, you know, I broke my neck riding a horse.

MATT: Recently too. Right?

ELISE: Yeah, recently, last year. These things can happen on horses, it's a dangerous sport, but yeah, it doesn't freak me out. I wouldn't like climb Denali the way that you describe in the book, just as like a, let's just pull over at Denali and like climb it, and that was scary reading about, I do have a fear of avalanches. I don't go back country when I ski. But, but yeah, I'm a pretty adventurous, at times, aggressively adventurous person. And I do not feel constrained at all by fear. But I'm not a daredevil. I don't have the tempting of death that you have and I wanna talk about your dad as well, so don't find it incapacitating. And yet in the moments when I do find it incapacitating like you, I also have learned to over function over my anxiety and to push through it rather than listen to whatever it is that it's trying to tell me. But it is misplaced, right? Like I don't have the fear where I should have the fear. I only have the anxiety of moments when I'm like, really? Let's not do this right now.

MATT: I don't wanna psychoanalyze you or any of us out there, but we wouldn't be able to function if we weren't able to override that anxiety. Like, the concept though, I mean, it is really cool and special that someone who breaks her neck, like you could have been Christopher Reeves, right? Like it could have been a much worse outcome. Yet the very next summer you're back out there. Not just like trotting daintily on a horse in a ring, you're out on a trail. It looked like a single trail too, like a small trail riding really, really fast. And so look, this is success, right? Like there is something in our brains that's evolutionarily wired to make us not afraid of doing certain things like we had. And, I'll come back to the whole chemical aspect of panic, but, you know, we had to be creatures who were able to put bodily fear aside to go out and spear the mammoth. Like I definitely would've been, I'd like to think, one of those people who goes out there foolishly like, oh, I'm gonna go kill Mammoth. You know, like taking the spear and like lunging towards the mammoth. I also probably would've been the person who would've tasted the mushroom like, oh, that looks good. You know, it may kill me, but maybe I'll have a really good time on this interesting looking mushroom and then, you know, provide support and, you know, it could also be a tasting mushroom, not just a hallucinogenic one, but I could, you know, make my tribe, my cave group stronger by helping take down the mammoth or finding a new delicious mushroom that's edible.

So we need that lack of fear, and maybe we also need the spasms of anxiety to temper that, so like the chemicals of it are super interesting, right? The chemicals or fear are actually engineered to make us survive, right? So what you get is, is you know, you get a jolt of adrenaline and you do that because your body is assessing a threat. For me, you know, the threat that my body is most afraid of in the immediate sense is the judgment of my peers. And so when I go live on air, and have for many years, that would be my brain at that moment starting to seize up and assess threat and say, okay, this could be really bad. Your group, which is these highly intelligent, super professional top rate people at ABC who are in this dimly lit cave of a control room in the upper west side, this is my cave group, and I'm there to make them stronger and failure on my part would make them weaker.

So there's a lot riding on it. So the brain tells my body, you're in trouble. This is a threat. Get ready. And it releases adrenaline epinephrine that gives you the jolt. I'm not gonna get into all like what parts of your brain do it, but basically those are the oldest parts of your brain that get into hyperactivity. Then in order to keep that strength going, so in the first initial seconds of an adrenaline jolt, and this can happen when you're driving in a car and you know, a tractor trailer flips over in front of you, your body assesses, your brain assesses the threat, it fires adrenaline all over so that you have strength in your muscles to keep running it. It gives you the ability to withstand pain to a certain degree. It gives you really impressive geospatial awareness, like your internal gps is on steroids, and it limits your ability to have long-term memory. So anything 30 seconds or longer is considered long-term memory, and that's pretty much wiped out, which is why sometimes we can't remember exactly what we said and then cortisol pumped in later to allow you to continue that flight if you need to, you know, in case a lion has bitten you but you've gotta keep running. Your inflammatory response is massive, et cetera, et cetera. So like you have this superhuman response, which then leaves you kind of depleted later cause you're tired. Your body has burned a lot of calories mounting this response and then it all subsides and works through your system and it takes 30 to 45 seconds to work, for your body to sort of work through adrenaline, which is why even after an initial jolt, you’ll feel the trembling going away. And it takes a little bit to work through it. It's not like an immediate end, but it was super interesting to me.

ELISE: But let's go back to something you just said that was interesting, that feeling of you're in trouble because I always feel like I'm in trouble. Anytime someone calls me or texts me and says, hey, do you have five minutes to talk? I mean, it could be my best friend. I am like, I'm in trouble. I've done something, and I wanna go to that instinct, that fear of judgment from your peers and go a step deeper, is it that it's about your livelihood and your ability to provide, I don't know if you were bullied as a child, is it going back to your dad, this becoming sort of quote unquote the man of the house as a 12 year old, and that that hypervigilance and performative child, was that a reaction or were you always like that? Were you always sort of the best little boy in the world?

MATT: Hmm. I mean, there's so much to unpack there. I was always the best little boy in the world, and that's why your book so resonated with me. I mean, I'm the flip side of on our best behavior, like that was me. I had to be on my best behavior. I'm gonna put that aside for one second, but, you know, in my effort, so I had this, this terrible reckoning in January of 2020 where I made a catastrophic on-air mistake during a live special report about the Kobe Bryant helicopter crash. And I'm not gonna get into it, outta respect for the family. And I was suspended for a month and I decided at some point after that that I had to either figure out panic. Obviously I had a panic attack, which is why I sort of blanked out about what I was saying and I made a catastrophic mistake, but I decided that I have to figure out panic or I gotta leave this business. Maybe I'll go back to print journalism. Maybe I'll just do radio, maybe I'll do something else, but this wasn't working because I was really, really unhappy and constantly afraid of melting down on camera, which made my life miserable and made my job miserable. And I really liked my job for the most part.

So the first thing I learned was about the chemical cascade that happens when we have a panic attack. And the next question was like, why do we have this at all? Like, how have humans in tens of hundreds of thousands generations that we've been around, not figured out that a panic attack is really not so good for us, both chemically, health-wise, mistake wise. Like not only does it feel really not good, but we are prone to make really boneheaded mistakes. And so like I went down this evolutionary rabbit hole and, cut to the chase. But, you know, humans evolved to be massively cooperative, right? The fastest human that's ever lived, Usain Bolt is slower than a hippo, right? A hippo runs faster. We gave up muscle mass and speed and size and whatever it was to have this amazing brain. And the biggest gift that this brain has is the ability to communicate in a way that no other animal in the catalog of Earth has ever been able to match. And we depended on that cooperation. So we first, you know, we had, pairings of a male and female at the time, that was why a lot of scientists believe that we became bipedal, like why we started walking upright, because keep our, our children and our offspring and our mate safe was better to keep them in one location rather than bring them to the site of a kill.

So we learned to carry stuff to bring to our people and then we started expanding that circle, cousins and kin, and then people who were just not related, but part of our group. And so the cooperation in that group became everything. And so there were two main buckets of human fear. One was being on the Savannah and getting eaten by a lion or having your offspring fall or drown or whatever disease, some terrible thing that would happen, but it would be physical in manifestation. The other bucket that was pretty much as scary was being ostracized, being banished from our group. Because if you were in a cave group or some group in the Amazon, and you were banished from the group, you were as good as dead because we were not so capable alone out on the Savannah. And so essentially as you'd get kicked out of the group by breaking some taboo, and you'd be walking alone on the Savannah whereupon, you would be eaten by a lion anyway, so the fear of being banished became as powerful as the fear of being eaten by a lion. And so that's why we have, genetically, so many of us, a massive social fear because it does matter. We do depend on these groups for a lot. You know, do we wanna have catastrophic panic attacks that might get us fired? No. You know, that's not such a great thing. But to have this kind of fear is normal. It's literally how we are designed to be. We need to be in these groups and we need to be cooperative members of these groups. And failure to do so is really, really bad.

So understanding that helped me think, okay, hey, I'm not like this totally freakish kink in the human genome. I'm just like a normal participant in the genome, and I happen to have these very powerful, panic attacks, but the brain is wired for us to have a thousand, I’m giving a number, but this is what the evolutionary psychiatrist Randy Nassi says, you're basically wired to have a thousand false alarms rather than to have one missed alarm, right? So if you're in your cave, you want to be wired to freak out and be really, really careful of other people’s rather than break a taboo and get kicked out of the cave and be eaten by a lion, so like your brain is saying, okay, like you have a panic attack and you burn 50 calories. You break a taboo, you miss a social cue, or you miss some other alarm, and that's 125,000 calories, which is the sum total of a human body if a lion eats it or any animal, so we're wired this way, and that gave me actually a lot of peace. You know, and you ask about like my dad, or like why am I so finely attuned to these kinds of social pressures? Why does the group matter so much more to me that my brain goes on the fritz when I'm at any risk of violating what I think may be a taboo? And I'm not sure. I mean, it could be like just being born that way and my parenting was part of it. My parents, you know, very much inculcated the fact that I'm a very good little boy and I bring them a lot of pleasure. So keep doing that. We'll keep reinforcing in you the sense that doing good and being high achieving is what we like.

ELISE: I mean, this is a wild theory, but just thinking, putting ourselves in the same bucket too, and I'm not, again, I am not covering war zones. But I wonder if anxiety or fear exists on a spectrum and that you have to have a certain amount, you need to process and express a certain amount of fear and anxiety and that we are lacking maybe in the physical side or where we feel like we have more physical mastery. And so it all comes out on the emotional, that if we were more modulated right, a little bit more fearful physically, that maybe we wouldn't carry so much on the mental sort of amorphous delocalized anxiety. Who knows? That's just one theory.

MATT: It's a really interesting theory.

ELISE: Maybe it's a spectrum. One a reason that I think too, your book is important and important for everyone, but specifically for men who I'm sure highly identify with you as this an example a man, right? Like doing things in the world, being brave, and being visible in that bravery that to actually talk about it and name it, and you talk a lot about this, the absence of support groups, the fact that it's not discussed, I don't know if you're familiar with Terrence Reel's work, Terry Reel's work with men, but he talks about how when you look at rates of depression amongst men and women, women seem to completely over-index. But once you add in deaths of despair, suicidality, addiction, personality disorders, there's equivalences. And so I think there are so many men like you, it's not an affront to my femininity to admit my anxiety in the way it is. I think for men to acknowledge that they feel weak or powerless in the face of anything. So it's a great service for you to acknowledge this because I'm certain you're not alone and also the fact that you're such a good crier. Can we talk a bit about your journey as you moved past, you know, drugs past psychopharmacology to find the deeper root cause of why you were hijacking your system?And I don't know if you feel like you got a satisfying answer, but it does feel like you really actually started to process a lake of grief inside of you. Um, will you tell us about that very exciting part of your journey, barfing in buckets?

MATT: So there was so much, there was so much discomfort. I wanna get back though, to something, and maybe you can ask me in a little bit and I'll go through this first, but how endemic this is, the sense of not being alone, which is like a really major part of this journey was figuring out that I'm, I don't have a a constituency of one. It's like they're all these people and it is so many men. And it was like of all the people who like, you know, crypto panickers who like, man, and in the middle of the night, you know, like people can, like massively wealthy CEOs and people who you think have not a care in the world are the most well adjusted. The people who have everything going for them wake up with terrors in the night with panic attacks that they just can't figure out. And so what do they do? They take the Xanax or Klonopin or Ativan or whatever drug it is that the psychologist is psychiatrist is providing and there's so many more of them out there than anybody anticipated.

ELISE: Tell us a stat on the people who show up at the emergency room thinking they're having a heart attack.

MATT: So 30% of all people who arrive at the emergency room thinking that they have a heart attack are actually having a panic attack, 56% are having anxiety or panic related issues along with whatever else is wrong, and most of those people who arrive thinking that they're dying of a heart attack when they actually have a panic attack are sent home without being told that they had a panic attack. And so for people with anxiety, it just ratchets up their fear. Like, okay, my heart's okay, but maybe it's my kidneys, or maybe I'm having an aneurysm or you know, a stroke, cause that’s what it feels like. And you know, I interviewed this 17 year veteran of the Shasta County Dispatcher's office. In 17 years she was on the phones listening to people calling in with heart attacks and panic attacks, and she said the symptoms are almost exactly identical. People having pain in their chest, having trouble breathing, breathing either really shallow or really fast. The sweating, the tunnel vision, the shaking, the derealization, all of these symptoms essentially mimic a heart attack, which is why so many people present at the ER with panic symptoms, but actually think that they're having a heart attack. And so, like, generally, like the latest surveys, which are kind of hard to pinpoint, but basically 28% of Americans are likely to have a panic attack in their lifetime, but the psychologists who study this every single day, like the head of the laboratory for Anxiety and Panic studies at University of Texas, Mike Chu have spent a lot of time with, is like, no, it's closer to 50% of all Americans are likely to experience a panic attack at least once in once in their lifetimes.

That's how pervasive it and so I thought, in this journey of mine, I'm like, okay, I need to talk about it. I need to tell people yes, Matt Gutman, the guy who's in war zones all the time, who's been to Ukraine twice this year, who's just in Israel to cover that conflict, who's been to Iraq and Afghanistan and Syria and Lebanon. This guy is afraid when he goes on air and he's having real trouble, I'm gonna tell people, I'm gonna confide in people and they've gotta be groups all over the country. But there weren't, there were five listed on the NAMI website. Two of them were defunct and only one of them accepted new people. And this isn't a country where there've gotta be, you know, we know that there are tens of millions of people who suffer from panic, but there's basically no one for them to talk to, which was really shocking and really sad to me. And so, and that's why every time I tell people that I'm writing this book, especially men, as you mentioned, Elise, they confide like almost conspiratorially, like, yeah. I've also had panics, you know, either public speaking or in front of my office mates or at the water cooler or very often it's more common than I thought going to the supermarket. People for some reason have a hard time with supermarket cashiers because of the pressure and I guess the forced intimacy of dealing with someone one-on-one like that. Anyway, so this is massively pervasive, and we don't have a lot of outlets, which is why crying was so important for me.

ELISE: Yeah. And it feels like part of that journey, you know, you ultimately came off of your antidepressant, sort of not knowing who you were before that, which requires its own type of withdrawal and SSRIs are a whole other conversation, obviously they work for some people, unknown how or why, and don't work for a lot of people or stop working because of the placebo effect. So you established a new baseline, right? Where suddenly you felt. From what I read, significantly more raw or less emotionally muted or guarded, is that accurate? Where suddenly you kind of have to confront more of your feelings?

MATT: That's very accurate. You very articulately put it, I was a bloody mess. I was a poppy, weepy, angry mess when I titrated from my SSRI, which was Paxil, which I've been on for 18 years. And I’d been concurrently try to figuring this out, evolutionarily and chemically. I was going to the psychiatrist who I'd been seeing and he and I for a couple years had been trying to work through panic. We hadn't talked about it a lot, it was just a lot about treating it chemically through pharma. And so I did try Xanax and I tried Propranolol and I tried GABAs, which are basically anti-seizure, some anti-seizure medicine. I tried a lot of stuff including, Adderall for my ADHD, which he diagnosed as well, which is, you know, giving a stimulant to someone who's got panic is controversial, anyway, none of these worked, and I'm not disparaging SSRIs or benzos. They do work for people. There are people out there you just mentioned for whom they are godsend for whom they enable them to live a fulsome and healthy life. And I'm so happy for those people. I'm not one of them. They did not work for me. I was still panicking. I was still feeling that death like vice around my throat, you know, Harry Potter's dementors seizing my throat with their bony fingers and squeezing the life and the words out of me. And so I needed something bigger and that if my first experience of an altered state was actually breath work, so my buddy, like right after my suspension's, like, you gotta come do this breath work class, like breath work. I mean, I meditated, you know, my parents took me to do TM when I was a kid, transcendental meditation. And I kind of kept the practice here and there in my own varied form for years. I'm like, breath work.

Anyway, I ended up doing this breath work with him and you know, you're chugging really hard in breath work and I of course dove in cause like if it's a physical challenge, I'm all in. And I just started bawling, just hysterically crying in this class with all these people. And I didn't care. I didn't care. It was so, oh my God. It was such a relief to be able to get emotional like that and to just let this pain gurgle and burble, and burst out of me. I'm getting emotional just thinking about it cause it was so freeing, and this was the start of I guess, my journey through altered states, right? I wasn't looking so much to get high. I was just looking to find ways to get me out of this head state that were big enough to basically knock out the conscious ego of Matt and, and get to something deeper. So there was, you know, psilocybin and ayahuasca and ketamine and DMT and basically all of them in one form or another enabled me to the, to get to, you do read your books when you, when you do these interviews, you do your homework, what you so accurately describe as the well of grief. It's like this place that was so bottomless and so dark that and the sober Matt, I always felt like there was no way I can go anywhere near there because I'm not gonna be able to claw my way out. Because I remember these bouts of weeping with my mother that we had in, in the weeks, the months, the years even into high school and college, I’d come home and we'd just sit and cry for two days and, you know, my dad was killed in a plane crash when I was 12, and it was like our world was lost. I was really, I mean, it was, it was traumatic in every sense of the word, and it had these cascading, ripple effects in our lives. But I couldn't go back there as an adult.I couldn't go back to that well of grief. It was, it was too damaging. It was too scary. It was too time intensive and so psychedelics really helped me to get there. And I will say part of how I learned about this or what reinforced it with me was your interview with Ellen Vora, ahead of her book. And Ellen says in something that I will never forget. We need a societal reframing of crying. We need to rebrand, crying. And it's so true. It is free. It is like the best relief that we can get and it's what our bodies are engineered for. It's a scary place, but it's certainly a good place.

ELISE: Yeah, so interesting hearing you talk about that well of grief too, and then thinking about what you do and the way that you walk that line between life and death, that tightrope, although it seems like you really wanna live, and then the way that you're front row, right on so much devastation. You talk about Yuvalday in the book and having to witness, and not only witness, but then package and present incredibly hard things to the public also requires a lot of management of your emotions. But almost to the point, you know, I sometimes wonder like, what's also the responsibility of the way that we talk about these things, and I know that there's been so much conversation about school shootings, for example, and like, do we break a social norm where we actually see the bodies of what's happening, what’s required to sort of snap people out of it. Yeah. And people, you know, acknowledge how traumatizing that would be for the rest of us. And yet we're also by not seeing it allowed to make this so abstract. Right. So anyway, I know as someone who's present, right, like you are viscerally in these experiences, I can only imagine how that well of grief has expanded over the years of all of that other unprocessed emotion.

MATT: I talk to these people, Elise, and I know there are a lot of journalists who can do it as well, but I think it's one of my gifts is to be able to speak in our mutual language of grief. I know this language, I've been there. I know that there's a lot that you can't actually say that the words don't mean anything, but you know, you communicate a lot through your eyes and just being there with people and it's the hardest thing I do in my job, and it's also one of the most important. And yeah, like I am the depository of a lot of other people's grief, including my own, and that's part of what we do as journalists, especially now dealing with literally the most horrible thing that I can imagine dealing with on this job, which is, or in society, which are the school shootings or any shootings in which children are murdered. So yeah, it, it takes more work on my part to figure out where to deposit that I added grief than that I deal with. But like in your job, I mean, you're also talking about people's grief and you're talking about their anxiety and their pains a lot, obviously ways to get out of it as well, but that's part of the bonus is like we are, we feel like we're giving back to society, and when we are contributing, it actually makes us stronger as well.

ELISE: Yeah. Well, and I think that your willingness in this book and generally to not bypass, right? And it seems like you were trying to bypass for a lot of your life or structure over, or dampen or manage armor against what was eating you from the inside out and to actually dive into it, I thought it was so interesting too the way that you describe in the book, the dosing that was required and just sort of your, have you read, I don't know if you've read, The Myth of Normal, but Gabor Mate talks about, it's like the most stunning part of the book when he talks about how, despite leading Ayahuasca retreats, it didn't like quote unquote work on him until he had, he was sort of pulled out of a retreat that he was leading and put in his own building and told that he was like so swampy, so full of darkness, and grief and just sludgy that he was a danger to the other people he was leading. It's a really beautiful story if you haven't read it, but like that they broke him, I mean, in a beautiful way in that journey. But I'm wondering, I don't know if you've gone back, whether you've, you've been able to armor against the drug or it has broken you down. Or you really think that you don't have the molecules?

MATT: Yeah, folks out there, there is a theory. There is a theory. Mark Strassman, who wrote the book called The God Molecule. And by the way, Goor Mate is an unbelievable person and a great writer. And his experiences is remarkable also cause he dealt with more trauma than I think any of us can imagine as a child. But we digress. So crawling over in this Peruvian retreat in the Andes Mountains as everybody around me is experiencing like literally sequin, harlequin gremlins. And a man was, he was taken by gnomes on a tour of the history of civilization and taken to see God, another person made intergalactic soul sex with his wife and bestowed all of the love of humanity on his son. And I'm sitting there with my eyes open three, like three times the doses of what all these other bozos had been taking. And they're like, yeah. Oh wow. And I'm like, huh, I'm not feeling is, is this thing on? I'm not what? I don't think I've had enough. So I crawl over to the facilitator, not the shaman, and I'm like, I think I need more. And it's like, now she's given me another half cup. So I'm like three and a half or four doses in. I would eventually do five times the dose that all these other people were taking, and she's like, I think you're blocking it. I'm like, I'm not blocking it. I'm open to this experience. I'm open. I please, I'm open. Oh my God, it was so painful. And I'm literally there. This is then I ended up taking another cup afterwards. So I'm five cups in, which is a massive dose. And the harmine chemical in ayahuasca basically makes your body open to accepting the DMT molecule, which is the hallucinogen. So, but it does that by ripping up your guts. And so I am writhing in agony on the floor, literally pooping my pants in this experience because it all comes out of you on both ends, and I'm just unable to let go and I never actually fully had the ayahuasca experience. I've resisted mother ayuh on the three occasions that we met, I apparently fought her off. But there are studies that say that even that physical experience that I had, the purgative experience is healing. And it was because I kept that dito, which is, you know, a very acidic diet, that they prescribed to you during and after I, your ayahuasca retreat for a while. I wasn't drinking for like six months and I felt really good. I felt cleansed and I felt very clear in my mind in a way that I hadn't been after that experience. I was like, ladies and gentlemen, I had diarrhea for 10 days after I came home from Peru. I could not get my system back on track, but it was healing. Eventually. I lost a little weight, but it was, it was very, very healing. A lot of the other drugs that. Medicines that I took were a lot easier and more palatable but Ayahuasca was very brutal, I guess. For lots of people I know, but I may go back there again. I don't know.

ELISE: I know, I'm curious. Well, I'm curious if you've been broken down enough to stop blocking it, because it seems like it feels like it could work on you. Meanwhile, I mean, I'm so sensitive. I mean, I don't know that I could, I’ve never done ayahuasca. I don't think that I could. I don't know if I could do it. It's interesting to me because I feel like it's really, I ayahuasca seems exceptionally good for men who need that sort of ego death. Whereas as a woman, I feel like I need to be, I feel so expanded that I need to be embodied. Like my instinct is to disembody or dissociate. And so I almost feel like I need the opposite, not to be sort of blown outta my body, but to be brought back into it.

MATT: Not to get too woowoo, but it's, it is very interesting. You know, it's mother ayuh and there were 12 people on our retreat and 11 of them were men. And there's something about men needing to get, they call ayahuasca, like I know Ayahuasca's the drug that just slaps you upside the head and tells you what you need to know. It's a very rough mother, but it's the treatment that a lot of men need, so I think there's a lot of truth and, and sensing what you're saying about that. Haven't thought of it that way.

ELISE: And then there’s father Iboga, Ibogaine, which hopefully someday they bring this, they legalize it and they bring it into a hospital setting, cause that can really stop your heart. It's dangerous not with medical intervention, but that father Iboga, in terms of addiction is just stunning what it does for people. And I wish that they would legalize it so it could be safe for people, so that they're not in the jungle, trying to recover from heroin addiction. But it's really stunning. But I also think that that's primarily taken by men. Meanwhile, I like MDMA, I like the gentle loving embrace of being here now.

MATT: Yeah, well, By the way, for all those folks listening, and I think you too, we're doing this not recreationally, like MDMA, the mescaline, all these medicines and we call them medicines or you know, people who've experienced them because they heal you. But I did all of them under the care of a facilitator or an actual psychologist who was there watching me. This is not like fear and loathing in Las Vegas, you know, when I'm slaloming around in a red caprice, you know, popping pills. Like I took this very, very clinically and very, very seriously, even though some of them were fun, like ketamine was really interesting at times, even though I had ego death and literally experienced, I mean, and literally, but I figuratively experienced what had to be death. It was very powerful, but some of it was very pleasant. So it doesn't all have to be nightmarish, although I had a lot of the nightmarish stuff just because I've got all the stuff that I've gotta excavate and I've been holding in for so long. But I think ultimately the idea is to find ways, as you were saying, to do it safely, to do it with people you trust it. It's very important to be with facilitators you trust, and to take it seriously because these are serious medicines and they will kick your ass if you're not ready for them. And they're not to be taken lightly.

ELISE: And they can be addictive in their own way outside of the chemical attributes and a form of bypassing. I mean, I have done through three sort of the MAPS protocol of MDMA, I have tried DMT, I have done ketamine and mushrooms, but I haven't done anything in years, and I feel like they're amazing at shining a light on where you need to look and that the rest of it is on you to integrate into the horizontal world and I have a lot of concern for people who use them all the time because how are you even integrating what's happening? And also like, we're supposed to be here, not there. And then I worry about the people who use these drugs and then become grandiose and the gurufication or the grandiosity that can come if you don't know how to contextualize some of these messages of like, oh, you're divine. Yeah, we're all divine. You know, sort of like you're special because we're all special. And then I think you see sometimes, particularly with people who have power in the horizontal world, where they're like, I alone am gonna solve humanities problems because, you know, I'm divine and I run a tech company and you know, like, watch out like that freaks me out. I see that a fair amount where it's like, oh man, let's not like pump up any more grandiosity here. Like, we need more humility.

MATT: I wanna know what your five MEODMT experience was like.

ELISE: So I've done it once and I didn't know what I was getting myself into, I did it with the facilitator, but my husband had tried it years before and had a very beautiful healing experience, but again, he's a man. Like, I think that these things are different for someone like him than it is for me. And so what happened to me is that I took it and then I was soaring above a temple and I was like, oh, you know, this is amazing. I was, I think a bird, and then I had sort of a fleeting, oh my God, where are my children. And I panicked. I panicked. I was like, I cannot go. I cannot be dead and leave my kids. And then I fought it and I ended up in a carwash full of dirty water and plastic toys.

MATT: Hold on, this was in your imagination, like in the trip.

ELISE: Mm-hmm.

MATT: You went from soaring over a Buddhist temple to, in a car dirty funnel.

ELISE: Water and plastic toys. Yes. And I was like, I knew at that point that I was having this experience and that I was not dead, but it was just that moment of death was, if anything, it just showed me how attached I am to my children and maybe hubristic because they'd probably be fine, but I just really, it went south fast, but then it was funny, but I did not enjoy it, and I have no interest in doing that again.

MATT: Interesting. So I started the journey, you know, you're sipping this stuff and in Peru they did it in this giant beaker lit by a butane torch. And the smoke is bubbling up and it's like a syrupy smoke, which is not pleasant to take down. And then I went to a pleasant place. There was like a brown curtain that was pulled across my consciousness and it seemed very nice. And suddenly I immediately I had this some sort of death experience and I immediately flopped out into the world like a newborn, sweating and screaming. And this was one of my most cathartic experiences. I just basically didn't stop screaming for 45 minutes, and like everybody on the retreat is outside. And I'm just like, it's just like this. Oh my God, it was so embarrassing. But I needed to extricate this stuff. And I had a facilitator there who was just holding me and, and they were a little bit scared cause I was having a very bad, very loud reaction. And at one point, one of the other guys like, Matt, please shut the fuck up, but it was 45 minutes of just screaming, but again, you know, everybody has these vastly different experiences. You just need to be safe whenever you're doing them.

ELISE: Yeah, safe and to have the proper integration and support so you can extract, I mean, I think it operates on two levels and, and ketamine obviously does because there's that neuroplastic agent for depression and complicated depression where it just suddenly people lose suicidal ideation. Like it can be incredibly powerful even without any psychedelic experience or a meaning making journey. So these things, and as you were saying, even just the ayahuasca, like the purgative part of it, whatever it did was healing, so there's sort of that, that baseline that you can achieve through those experiences. And then there's sort of the mind and the meaning that you can make from what you're shown or not shown. You know, they're interesting in that way. I think that they can either deliver, was it your wife who like essentially got like the mother of all messages about redirecting her entire life?

MATT: And she did. Mine is just like all pain. But I mean, maybe that's, that's the way it's supposed to be. And I think, you know, you mentioned integration and that really is key, and so, you know, after a lot of people do a psychedelic journey, you really should sit with a therapist or somebody who helps you integrate, which is literally talk about your experience. And hopefully it's more than once and I like, I'll often tap into those experiences when I do meditation. I don't meditate. Like I don't do 20 minutes, I'll do like 5 or 10. But I can find those moments, the, the nice ones, not the, like the screaming ones. And I find those moments and I can reanimate them and it's really pleasant and peace giving and so that's something I've taken from the integration and the psychedelic experiences that I can practice in a day to day. Cause you know, you can’t inhale smokey toad venom on a daily basis. It's not practical.

ELISE: I know we're running over, but my final question, do you feel, and I know that the book does is very responsible about not offering a pat, I did this, do this, you'll be fine but, where do you feel like you are on your journey? Do you feel like you're at the very beginning or in terms of really understanding what's driving you or do you feel at peace?

MATT: I don't think I feel at peace. I don't know if I will ever feel at peace. I feel better, I know much more I'm able to deal with the stuff when it comes up in a way that I was not capable of before. I've armed myself with these, or equipped myself with these tools that I didn't know I had but was capable of. I have, you know, a list of things that I can do in my head when I'm having an acute, so like 90% of this is living, a healthier psychological life, right? It's like not getting to the acute point where I'm standing in front of a camera and suddenly, you know, I feel like my jugular is about to like, pop through a tie or, you know, I literally can't see the camera in front of me. My tunnel vision is so bad. It's to avoid getting there. It's also knowing that I might very well have a panic attack on air again. Like, I can't say I won’t, it's a crazy experience but I also have all these tools to help me prevent, not get there and to forgive myself if it happens, right? Like, you know, I hopefully, I won't make, I'm pretty sure given what happened on that day in January, 2020, that the ingredients and that particular story are not gonna be replicated ever again like I'm pretty assured of that if I stumble and I don’t like my delivery, it’s okay. I’m going to be okay, we are going to survive this. You know, I have little tips that help me not only forgive myself but get through it. The concept that a panic attack is only 15 to 60 seconds, like I can get through that. I can get through anything that is 15 to 60 seconds, and I know that other people can too. Also, if panic were as debilitating as I thought, no one could drive. People would not be allowed to drive in they were prescribed benzos or had any clinical history of panic, but because we do get through it, we are capable of it. You know I practice mindfulness tricks, what I see, smell, what my mouth tastes likes, what I hear around me. Now that people know I have panic attacks, the shame is gone to a massive degree, and all the other stuff helps as well. There are little things I can do when it’s acute and big things I can do day-to-day to live a more psychologically healthy life and physically, which I always have.

ELISE: Thank you, this was a pleasure.

After we stopped recording, Matt and I continued to talk about the gendered implications of panic. And I know women with panic disorders and it’s interesting to me because I know about their panic disorders, it’s not something they lead their conversations with in daily life, but it’s not a deep dark secret in the way that Matt senses it might be for men. And I think men are really programed for power, and to have everything under control, and to be dominant, masculine, and the reality is, ultimately we’re all just human and we’re all animated by these very basic instincts and impulses and what’s so wild about panic—I don’t have the same type of panic disorder, I have an anxiety disorder where I chronically hyperventilate, which I write about in On Our Best Behavior, because it’s debilitating in a different way, it’s very exhausting—but what’s interesting about panic is the way that it just hijacks your body and I think for those of us who are very attuned to our bodies, who are used to mastery, control, making our bodies and minds do what we want them to do, it can be so anxiety provoking, not ironically, to have a disconnection or to feel completely out of control, to not will your body back into conformity. It’s a very tight book, 200 page book, it’s really interesting, and he’s a very fun writer and I hope that people read it, not only those of us who have anxiety or panic or feel crippled by an inability to control everything we do every day, but by all people. It’s an empathy book and you never really know what’s going on with someone. Thank you, as always, for listening.